Celebrated for his expansion of postwar abstraction, Sam Gilliam elaborated on and disrupted the once-dominant Abstract Expressionist themes emerging from the New York School. Working in Washington, D.C. at the height of the civil rights movement, the artist’s physical transformations of painting were reflective of the dramatic sociopolitical changes occurring in the United States.

Rather than conform to expectations to produce figurative, political art focused solely on Black experiences, Gilliam chose abstraction as a means of engaging in nuanced conversations around identity, race, and history. His artistic debut came in the late 1950s when names like Pollock and Johns dominated the art world. After a brief exploration of geometric abstract painting, Gilliam developed his seminal “Drape” paintings. As the name suggests, these works drape across the gallery instead of hanging in traditional frames. The move from flat canvases to hanging drop cloths dip-dyed with pigments transformed Gilliam’s paintings into objects—part-painting, part-sculpture, and part-installation—that uniquely occupied the viewer’s environment and redefined what a “painting” is.

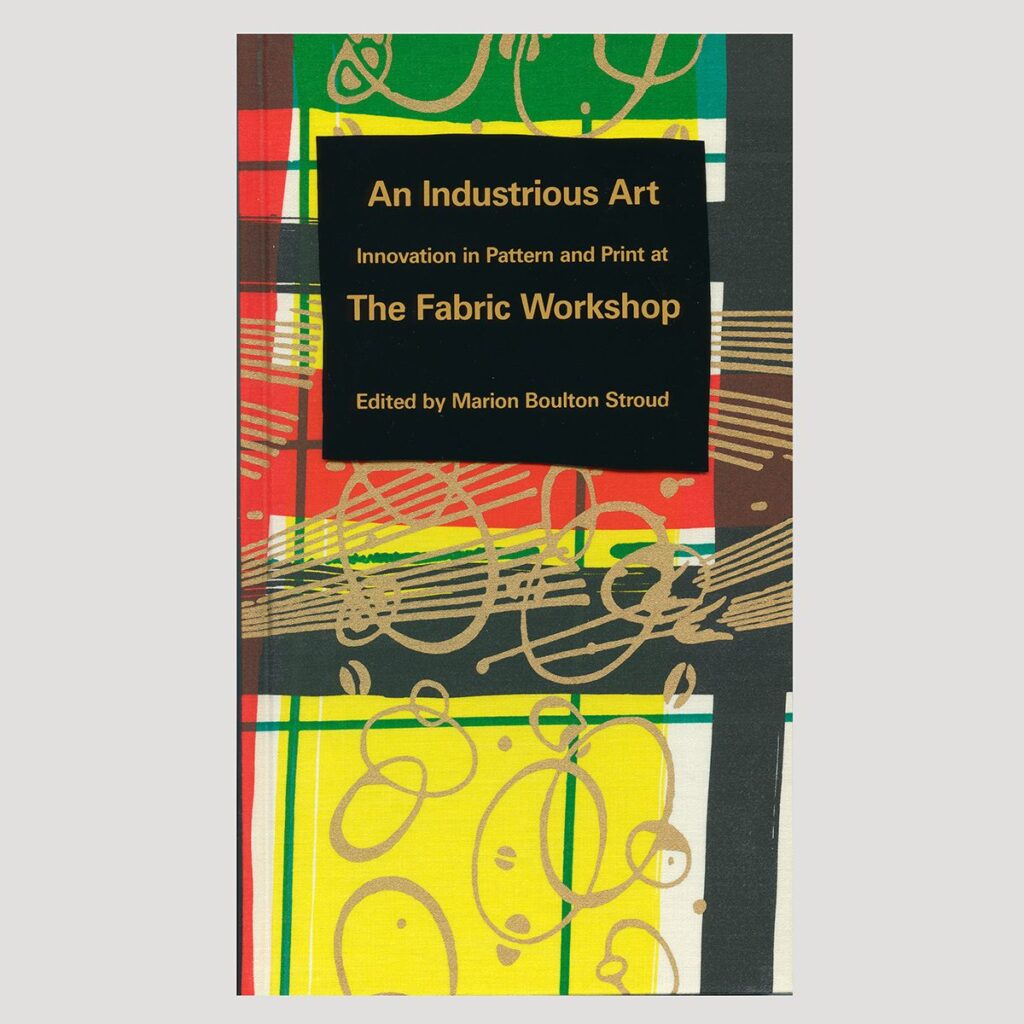

In the mid-late 1970s, Sam Gilliam produced several Philadelphia-specific works: first, a large-scale installation for the façade of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Seahorses (1975); and Philadelphia Soft (1977), a series of six linen and canvas works inspired by his time in the city that he created as one of The Fabric Workshop and Museum’s first Artists-in-Residence. Founded that same year, the workshop was focused on exploring the possibilities of a traditionally industrial process—screenprinting repeat yardage—as a new artform and provided contemporary artists with resources and materials for this exploration. During his time in residence, Gilliam employed FWM’s printing processes to produce the six related works, hand placing nineteen separate screens to create a layered, painterly surface. These pieces retain the physical characteristics of the unstretched and draped color field paintings for which Gilliam has become known, while utilizing a graphic mark-making approach characteristic of print. At the same time, the improvised and irregular use of so many screens resulted in related, but ultimately unique artworks—testaments to Gilliam’s subversion of both the industrial process and the aura of the masterpiece.